In 1845, Ute Indians came across an apparently abandoned Kiowa (Plains) Apache camp. On closer inspection, they discovered that a massacre had taken place. Only one person survived – a two-year old girl who was then adopted into the Ute tribe. They named her Chipeta.

Chipeta and her husband to be, Chief Ouray first saw each other in 1851 after Ouray’s mother died and his father brought him and two other siblings to Colorado. Ouray married Black Mare in 1853 and they had a son, Pahlone. Black Mare died in 1858 and Chipeta was chosen by the family to help care for Pahlone and the household. Her care pleased Ouray and they were married in 1859. Ouray was 26, Chipeta was 16.

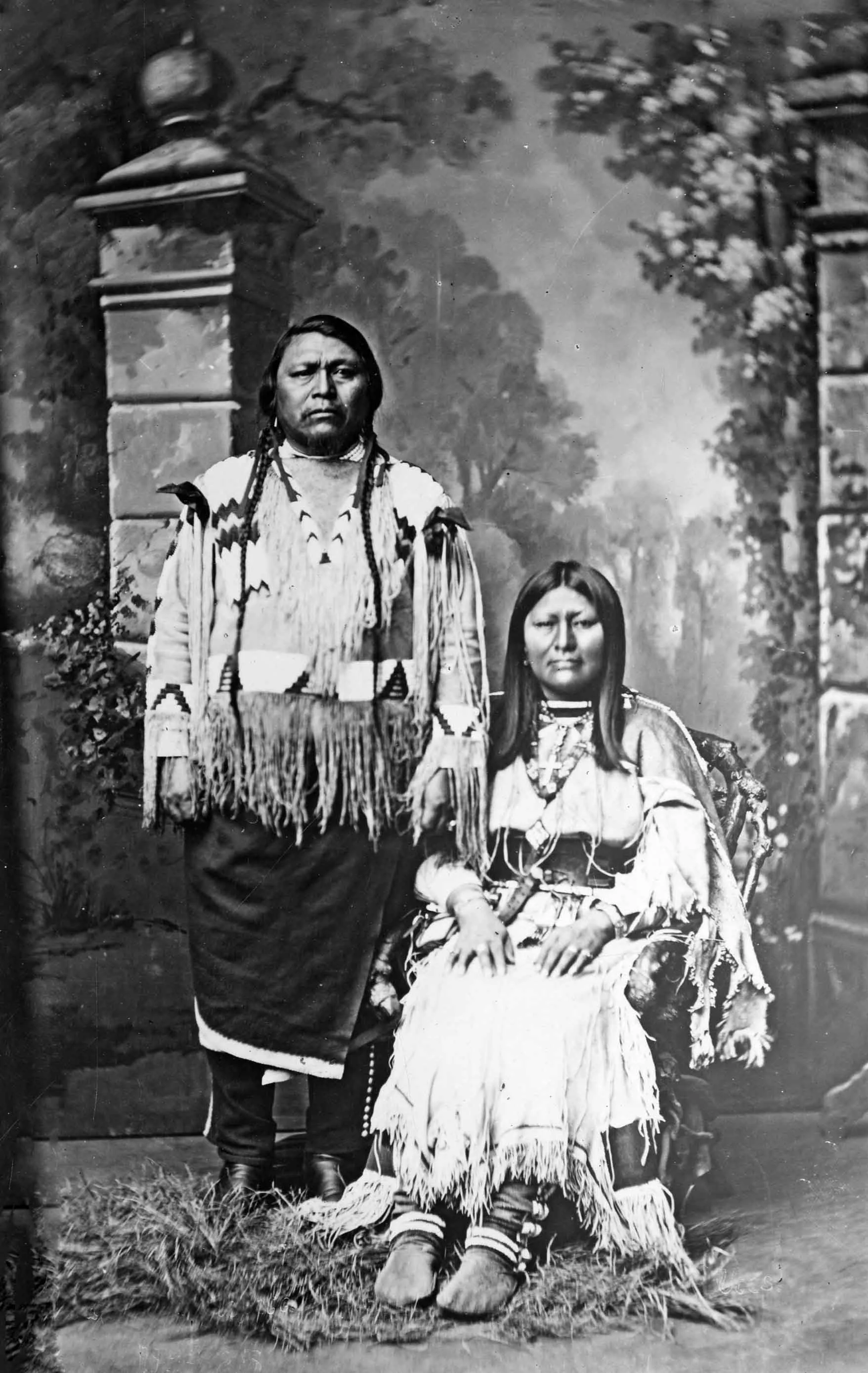

Chipeta and her husband, Ouray, were known as the Ute peacemakers. They were married the same year that gold was discovered in Colorado and that finding of “color” dramatically increased conflicts between Utes and whites. Perhaps formative warlike events in their younger years also contributed to their desire for peace.

Ouray was born in 1833 and raised between Taos and Abiquiu, New Mexico. One of his parents was Jicarilla Apache, the other Ute. He witnessed first hand America’s allegedly beneficial policy of imperialistic expansion – Manifest Destiny. He was a thirteen-year-old living near Taos when the territory of New Mexico, then under Mexican rule, fell to U.S. forces under Stephen Watts Kearny in August 1846. He also saw the Taos Revolt – a popular insurrection the following year by New Mexicans and Pueblo allies against the United States' occupation – get crushed.

Chipeta and Ouray were also friends of former Indian agent and Ft. Garland commander Kit Carson and his wife Josefa. Carson reinforced what Ouray had already seen – that the United States Army could not be defeated. Carson also told them that white people only recognized land rights if a piece of paper was involved. Thus he encouraged treaties, especially after Colorado was organized as a Territory in 1861.

Ouray thought in Spanish. He also spoke Ute, Apache, and some English. When Lafayette Head became Indian agent for the Utes in 1861, Carson recommended and Head hired Ouray as a skilled interpreter for $500 per year. Four treaties were created (and broken) in Chipeta and Ouray’s lifetimes. Ouray’s allegedly said of negotiations with whites, “Agreements the Indian makes with the government are like the agreements a buffalo makes with the hunter after it has been pierced by many arrows. All it can do is lie down and give in.”

In October of 1863, a treaty was signed where the Utes ceded their lands east of the Continental Divide (the Shining Mountains). Governor Evans then asked Ouray to settle disputes between Utes and white settlers. He had to travel great distances. Plains Indians had kidnapped Pahlone, Ouray’s son by his first marriage, during a buffalo hunt earlier that year. Chipeta loved him like her own son and was lonely. She asked to travel with Ouray, which was unusual at the time. Ouray gained a reputation among white settlers as a fair man. Chipeta was often Ouray’s only confidant. He treated her as an equal. When they went into Ute camps, Chipeta visited with the women and many times heard from them how their husbands really felt about matters. Chipeta was allowed in some camps when Ouray was not. She was the only woman invited to Ute Councils.

The signees of the first treaty did not form a representative group of Utes, however, so a second treaty was signed in 1868. It left the Utes with a rectangle of land west of the Continental Divide – basically the western third of Colorado minus the Yampa River Valley. The Tabeguache band of Utes to which Ouray and Chipeta belonged was given their own agency called Los Pinos near Cochetopa pass west of Saguache. Ouray got a house for being interpreter. He was also hired to hunt meat for the agency staff and thus had two government paychecks. Many Utes wondered how Ouray got such a good deal and speculated that he gave up Ute lands for his own profit. Several attempts were made on his life.

Indian agents came and went frequently and their quality varied widely. In May 1872, Charles Adams became the fourth Los Pinos agent in three years. He was a good one, however, and later played a key role in settling the problems caused by the Meeker Massacre. His wife, Margaret, and Chipeta became close friends.

Gold was discovered in the San Juan Mountains and whites clamored for more land. At first Ouray refused, but eventually the Brunot treaty was signed in 1873 and the mineral rich mountains were carved out of Ute territory. The Los Pinos agency was moved to an area just south of present day Montrose in the Uncompahgre Valley. The chiefs who signed were not told that the treaty named Ouray Chief of all the Utes and doubled his annual salary. The Utes in Colorado were a loose tribe of six bands. This did not sit well with some.

The fourth treaty came because of the Meeker Massacre. It was during this event that Chipeta truly shined as the divide between the Utes and whites grew wider. A combination of what Chipeta called “bad Utes” and an equally poor Indian agent, Nathan Meeker (who had organized the cooperative agricultural community of Greeley), led to the flare up. Meeker threatened to bring soldiers to the reservation to take disagreeable Utes away. In September 1878, a few White River Utes stole horses and shot a white man. Governor Pitkin requested military help. Ute scouts saw Army troops marching toward their land from Wyoming and remembered Meeker’s threats. Visions of the Sand Creek Massacre danced in their heads. A Ute chief rode out to talk to the Army commander and asked him and one or two soldiers to come to the agency to talk with Meeker. The commander refused. The Utes ambushed the troops and killed all the officers in minutes. When other Utes found out about the attack, they killed Meeker and the agency men. The women and children were taken hostage.

Ouray, already ill with a kidney disease that would soon take his life, was depressed by this turn of events. He talked about joining his brothers for one last fight against the whites. Chipeta spent the entire night talking him out of this idea. Ouray eventually ordered the White River Utes to retreat. U.S. Secretary of the Interior Schurz asked trusted former Indian agent Charles Adams to help. In late October, Adams rode out with a loyal group of Tabeguache men. He convinced the Army to leave the reservation. The White River chiefs released the hostages. After the hostages arrived at Chipeta’s home, they reported that Chipeta did everything possible to make them comfortable.

Ouray, Charles Adams, and another man were appointed by Schurz to make a formal inquiry into the incident. Ouray got permission to move the investigation to Washington, D.C. where a fairer trial could take place. Chipeta was named a member of the delegation. Secretary Schurz decided the whole White River band had to be punished for the deaths at Meeker. He assigned them to a reservation in Utah where the Uintah band of Utes lived. He moved the three Southern Ute bands to the very southwest corner of Colorado. He offered the Tabeguache Utes a smaller reservation where the Gunnison River and the Grand (Colorado) River met. The Ute delegates in Washington did not argue and signed the treaty. The Ute delegation had to convince three fourths of all Ute males to sign the treaty by Oct 15, 1880.

Ouray, who had stopped wearing white men’s clothes, also refused to take a carriage on the long trip to Ignacio to try to convince the Southern Ute bands to sign the treaty. The exhausting ride on horseback severely weakened him. He died on August 24, 1880. A Muache chief who usually opposed Ouray was then struck by lightning. Southern Utes took it as a sign and signed the treaty. The Tabeguache Utes did not want to sign the treaty either, so Otto Mears paid each Ute who would sign the contract two dollars and the required signatures were collected.

A team of men who oversaw the move of the Tabeguache band to their new reservation in 1881 had the power to move the Utes to another place if the Colorado River area (think Fruita) was not suitable for farming. Otto Mears, a member of the team, convinced the others to force the Utes to settle in arid Utah instead.

Chipeta married again and adopted six boys. The land they lived on was very poor. In 1916 a former Indian agent sent to investigate described Chipeta as “destitute.” He wrote the Commissioner of Indian Affairs recommending irrigation water for the parched land. The Commissioner sent Chipeta a shawl. Chipeta became a sort of celebrity in her later years and travelled back to Colorado for events and visits. She died in 1924 (the same year that Indians became U.S. citizens) on the Ouray reservation in Utah, blind, at age 81. She is buried near Montrose where she and Ouray lived until 1880.

Chipeta was selected to be on a centennial tapestry created to honor eighteen women who played important roles in the settlement and development of Colorado. It now hangs in the State Capitol Building.

by Wayne Iverson

Bibliography

Neither Wolf nor Dog: On Forgotten Roads with an Indian Elder by Kent Nerburn

Ute Indian Lands by Virginia McConnell Simmons

(Colorado Central - August 2014)

The Ute Indians of Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico

by Virginia McConnell Simmons